When it comes to mixing, there’s a series of problems associated with recorded sound and psychoacoustics that we need to be aware of in order to avoid common mistakes and achieve better mixes. To circumvent these problems, there’s a series of techniques whose effectiveness has been proven and validated over the years. This article will introduce both the problems and the techniques used to overcome them.

The first important fact to be aware of as a music producer is the major difference that there is between the physics of sound in the open, i.e. as produced by analog instruments in a live setup, and the physics of recorded sound. In a live setup, the addition of instrumental layers contribute to the overall loudness and energy of the music. In a sound recording, this works only to a certain point, especially in digital recordings below 24Bits. Beyond that point, all you get is squashed, lifeless sounds and distortion. This is because in a recording, there’s a limited room or space available, and we have to make choices about what we fill it with.

Another major consideration is the fact that the frequency response of the human ear is clearly skewed towards the mid-range and quite lacking in the low-end, the frequency range that by default takes up most of the available space in a mix, whether we hear it or not. No less important is the fact that sustained sounds contribute more than transient sounds to the overall perceived loudness of a mix, while at the same time take up more space, and are more prone to masking and mudding than short sounds.

Lastly, it’s important to realize that most of the sounds in a mix contribute to mid-range build-up. This is because the mid-range is the most common frequency encountered in most sounds. Therefore, most of the sounds we throw into a mix have some, if not lots of it. Add this to our acute sensitivity to mid-range frequencies and you realize how prone this frequency range is to masking and distortion.

So, how do we balance all these seemingly irreconcilable factors of sound and human perception in order to achieve big sounding, crystal clear mixes?

Sidechain Everything

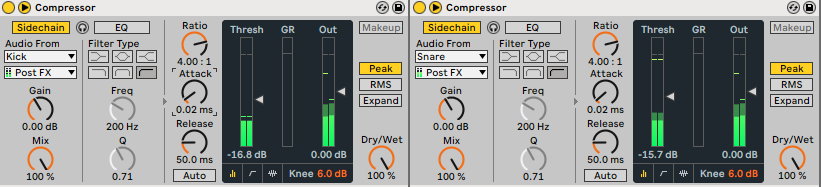

One of the most effective ways to avoid masking and mid-range build-up is doing extensive side-chaining in your mixes, and I don’t only mean the typical bass ducking you hear in every EDM track, I mean adding one or more dedicated compression units for the exclusive purpose of sidechaining in every single channel of your mix, especially in those prone to clashing in a particular frequency range. In general, the basic setup for sidechain compression is to use it on sustained sounds like synths and bass using transient sounds like drums as sources, but you can go beyond that and extend it by using it between other types of sounds that are prone to masking, like a guitar and a keyboard, or two similar sounding synth presets. There are no limits when it comes to sidechaining, as you can sidechain from multiple sources and even automate the threshold in order to alternate between source groups all throughout the mix.

Synth Loop With Sidechain Compression From Two Different Sources

Use Gates

It’s amazing how much clutter and rubble can be scooped away from a mix through a proper use of gates. When you start to use gates in your mixes you realize how much useless stuff there is in a mix that can be transparently removed allowing the sound to become cleaner, bigger and more focused. Gates are incredibly useful to control the tail of sustained and resonant sounds as well as time-based effects like reverbs and delays.

Gate Applied To Snare Drum Reverb Return

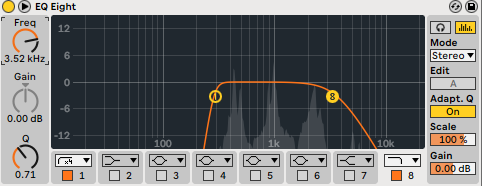

Use High and Low-Pass Filters

One of the key rules for clear sounding mixes is to have few elements with a clear dominion over a focused and narrow range of the spectrum. High-pass and low-pass filters help you achieve just that. Select a palette of instruments or sounds with a clear tendency to dominate their own frequency range and then reinforce that tendency with high and low-pass filters while opening up space for the rest of the sounds. This practice is particularly useful in the low-end below 30-40 Hz, as these frequencies are barely audible and all they do is take up space in the mix. You can and should insert pass filters in every channel of the mix, including return tracks and buses.

Low and High-Pass Filters Applied to Synth Loop

Process Short and Long Sounds Differently

Short sounds need to be sharp and tight in order to add energy to the mix without masking other sounds. In order to achieve this, we can use short attack and release times on amplitude envelopes as well as gates to control the tails. Another way to add more punch and clarity to short sounds is through the use of transient designers. These processors allow us to increase the transient energy as well as shorten the tails. Compressors are also useful to control the amplitude of the attack and release sections of a sound through their attack and release controls. Long attack times allow for more transient energy to come through, while long release times can make the tails disappear more quickly.

Long sounds, on the other hand, need to appear more gradually in the mix and feature more powerful sustain sections in order to contrast and blend with the short sounds. For this, we can employ the same techniques used with short sounds but in reverse.

|

Amplitude Envelope Drum Settings

|

Compressor And Transient Designer Drum Settings

|

Choose And Arrange Your Instruments and Sounds Very Carefully

This is arguably the most important principle to follow when it comes to improving your mixes, as it can mean the difference between a mix that practically does itself and one that is impossible to pull. The instruments and sounds of a good mix must be complementary and contrasting in terms of frequencies, character and length. If you think of traditional ensembles such as the Pop/Rock quartet, you find an enormous contrast between the four parts of the ensemble in every possible musical term, which makes mixing extremely easy. This minimalistic and highly contrasted choice of sound sources is the ideal model for perfect mixes. Choose your sounds with this model in mind and you’ll have more than half of the job done. In cases in which you can’t or refuse to take a minimalistic approach in your mix, try and group into different families those sounds that are prone to clashing and alternate them in the arrangement or stack them together in unison. Treat these groups of similar sounding sources like a whole in terms of arrangement and processing, so you get extended sonic variety without mudding the mix. Another useful strategy when working with similar sounds in a mix is to establish different level planes, allowing some sounds to dominate over others instead of trying to make them all sound super loud.

Summary

In this article, we’ve touched on the typical problems and challenges associated with mixing, as well as on a series of well grounded techniques that have arisen and evolved over the years to mitigate these problems.

Share this