This series touches on fundamental areas of music theory for music producers and beatmakers. We'll cover topics such as harmony, rhythm and arrangement, delving into intervals, scales, chords, rhythmic figures, patterns and meters, beats, and much more.

Learning basic music theory will enrich your productions and speed up your workflow, so let's get started.

Harmony

Harmony is the field of music theory that deals with the study of notes and the various ways in which they can be organized in time and in relation with each other and with other musical dimensions such as rhythm, form and timbre. Harmony can be developed horizontally through melodies and vertically through chords, and it has a profound impact on our perception of music, being able to evoke powerful mental images, associations and emotions.

Intervals

Harmony is all about relationships between notes, but what truly defines these relationships is not the notes themselves, but the distances between them, or in other words, their intervals. Intervals are the building blocks of harmony, and they can be strung horizontally to build scales or stacked vertically to form chords. Scales and chords built on intervals form powerful harmonic blueprints that can be easily transposed to other keys, making them more reusable than notes when it comes to laying out harmonic content.

Intervals are also used to measure transpositions, that is, displacements in pitch exerted on single notes or groups of notes with the intent of creating harmonic variations.

Intervals are measured in semitones, which is the distance between two adjacent notes in the chromatic scale, or between the two adjacent keys of a keyboard.

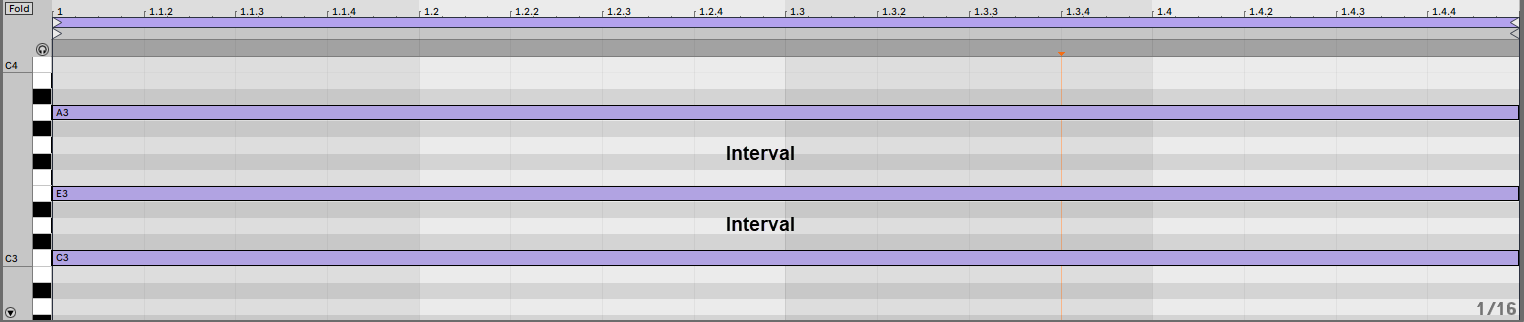

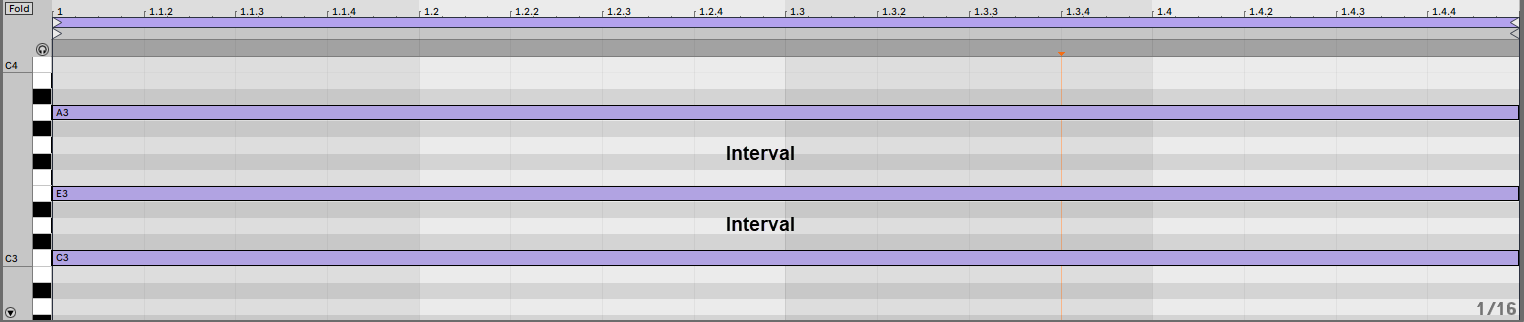

A chord built on two intervals:

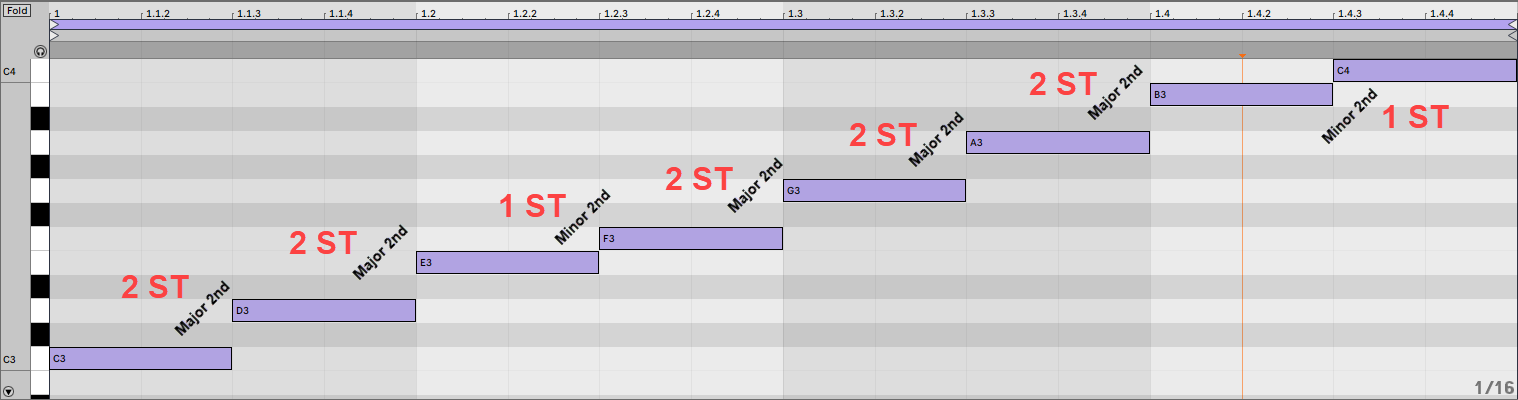

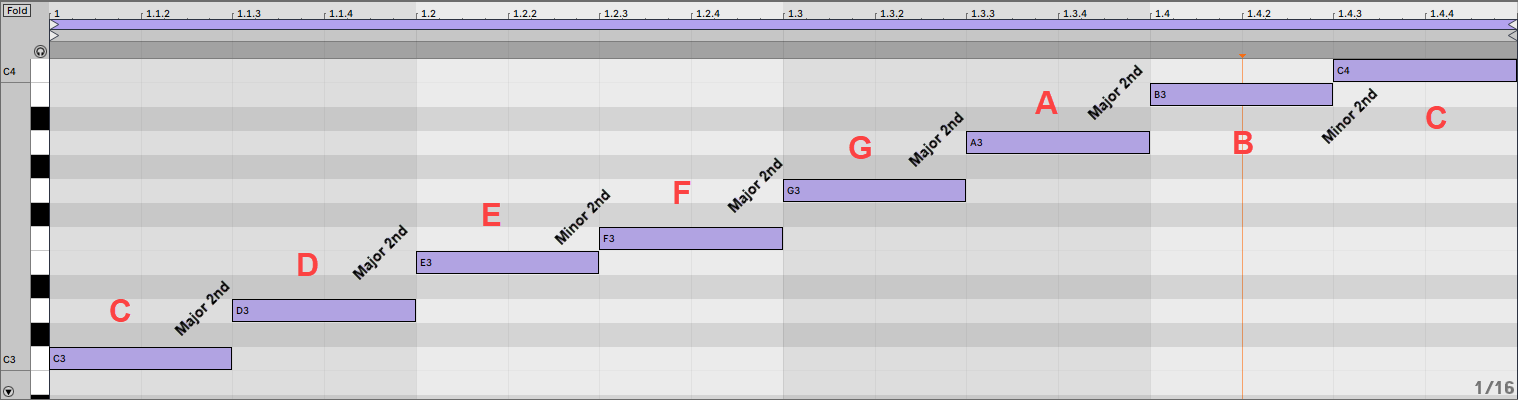

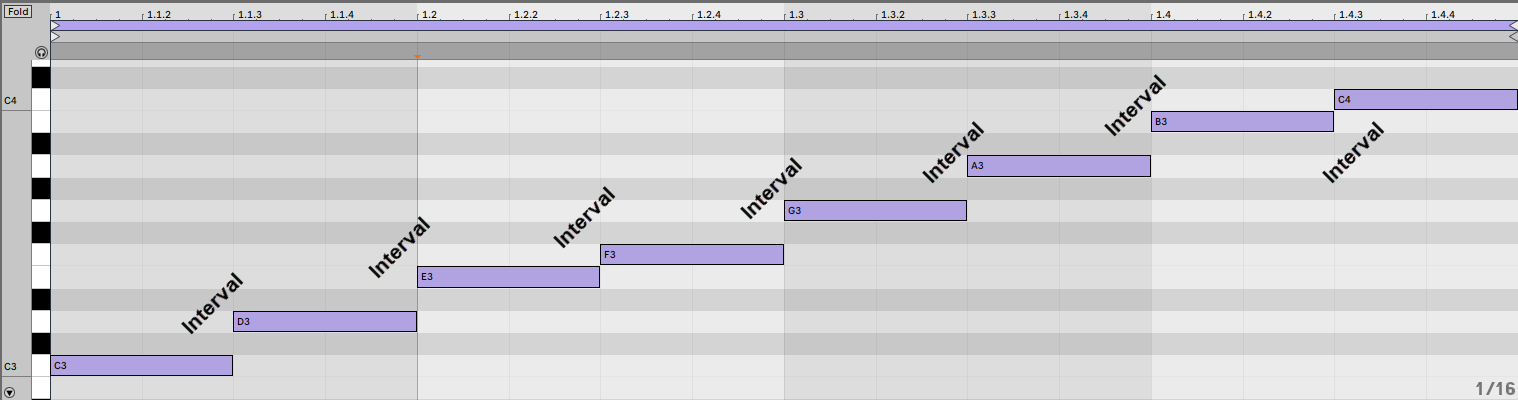

A scale built on seven intervals:

Interval Types

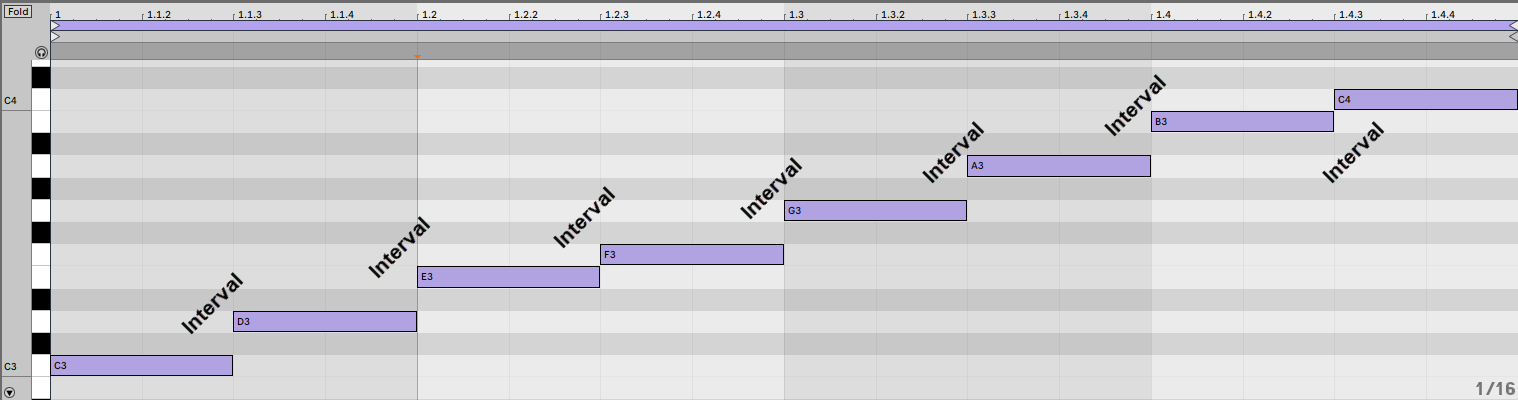

Measuring intervals in semitones can be cumbersome sometimes though, so there’s a set of interval types for various ranges of semitones that can be used instead. This method is more descriptive and easy to recall than semitone numbers, so it’s the most widespread option used to describe the intervallic structures of chords and scales.

The main names of these types of intervals are ‘second’ for ranges between one and two semitones, ‘third’, for ranges between three and four semitones, ‘fourth’ for ranges between five and six semitones, and ‘octave’ for 12 semitones intervals.

Intervals of second can be minor or major depending on whether the interval is one or two semitones long, the same goes for the intervals of third, with minor thirds for intervals of three semitones and major thirds for intervals of four semitones. Intervals of fourth are ‘perfect’ when they are five semitones long and ‘augmented’ when their notes are six semitones apart.

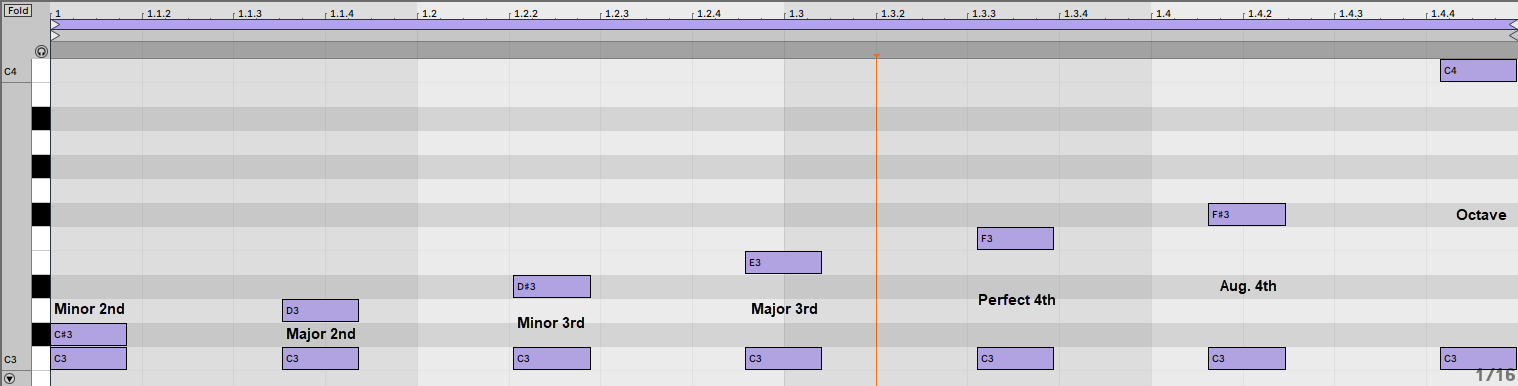

Various interval types:

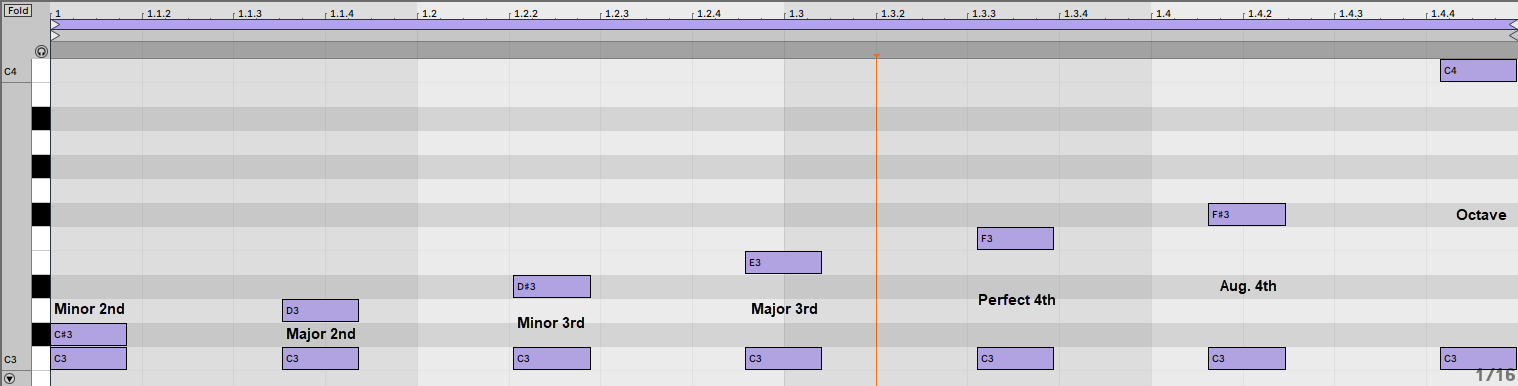

Inversions

Other types of intervals like fifths, sixths and sevenths are simply inversions of the main ones just described, this means that they can be obtained by transposing one of the two notes that form the main intervals an octave up or down, so for example, a second can be turned into a seventh by bringing the lower note an octave up or the upper note an octave down, and a fourth can be turned into a fifth by transposing the lower note an octave up or the upper note an octave down.

Inversions are very important when it comes to understanding chords in their various voicings, that is, the order in which the notes of the chords are stacked, as well as mastering voice leading, which is the art of building chord progressions based on the movement of the notes or voices of the chords, as opposed to the movement of chords as monolithic blocks.

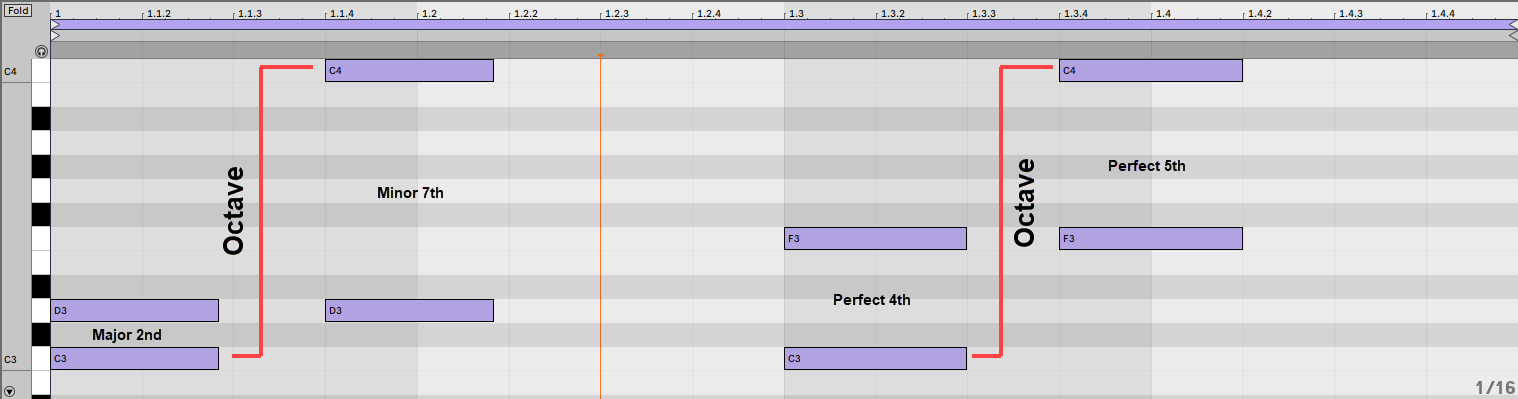

Inversions:

The Major Scale

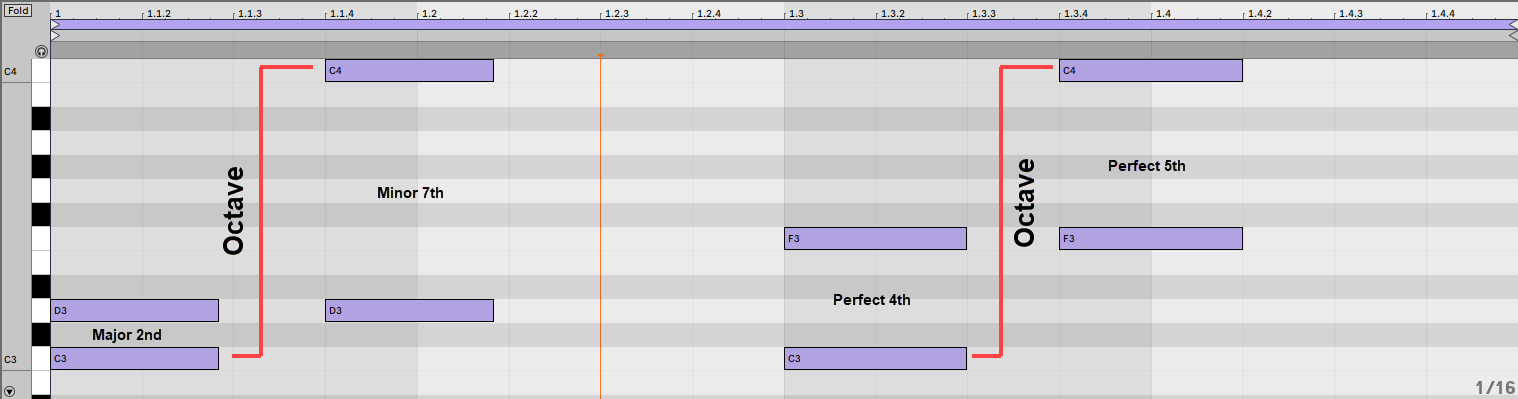

The major scale is the most important scale in western music and it is often used as a reference to build all the rest of the existing scales.

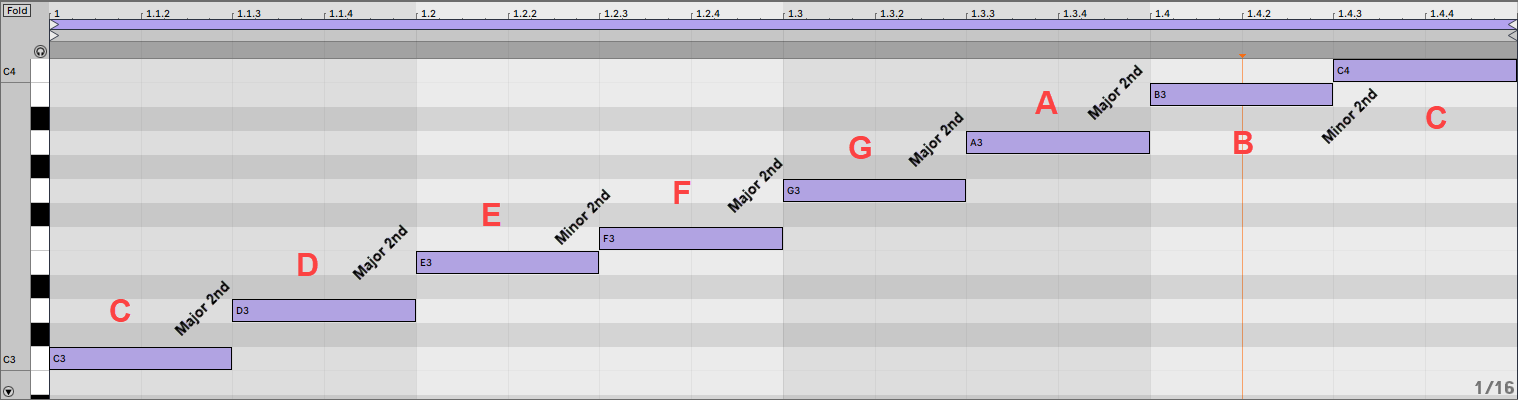

The intervallic structure of the major scale in interval types is: major second, major second, minor second, major second, major second, major second, minor second. This same pattern in semitones is: two semitones, two semitones, one semitone, two semitones, two semitones, two semitones, one semitone.

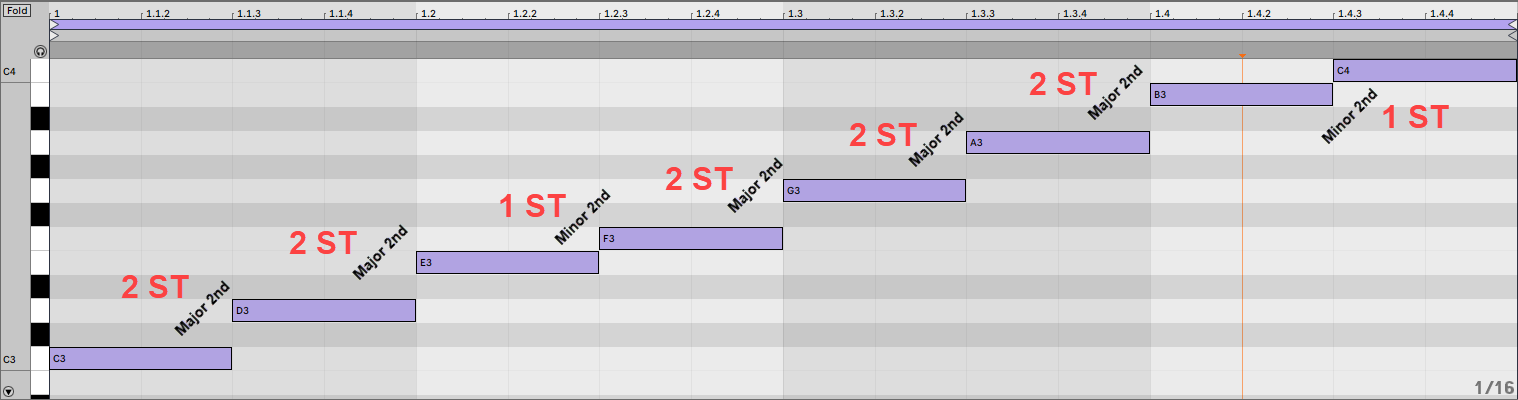

The Major scale:

NATURAL AND ALTERED NOTES

The scale of C Major has the additional importance of being the one that gives their names to the so called natural notes, that is, notes without alterations, which are the ones that can be obtained by playing only the white keys on a keyboard.

If we apply the major scale pattern of intervals on the note of C we get the names of the natural notes: C D E F G A B. We can then see that the natural notes are all two semitones apart from each other, with the exception of E/F and B/C, which are one semitone apart.

If we transpose these notes one semitone above or below their natural position, they become altered notes instead of natural notes.

When natural notes are one semitone above their natural position, we say they are sharp or augmented, and when they are one semitone below their natural position, we say they are flat or diminished. The symbols for sharp and flat are # and b, respectively.

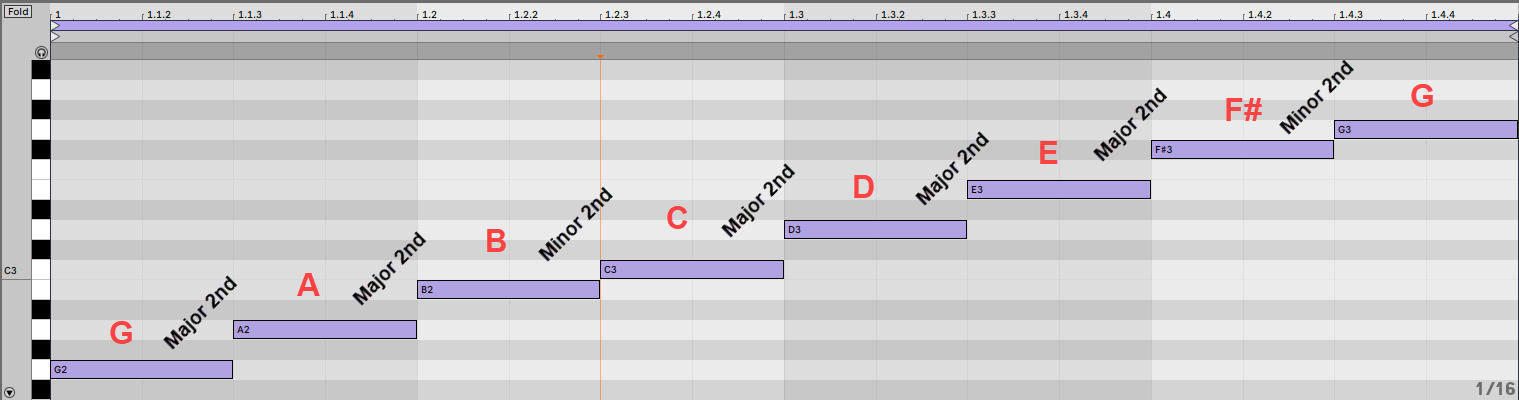

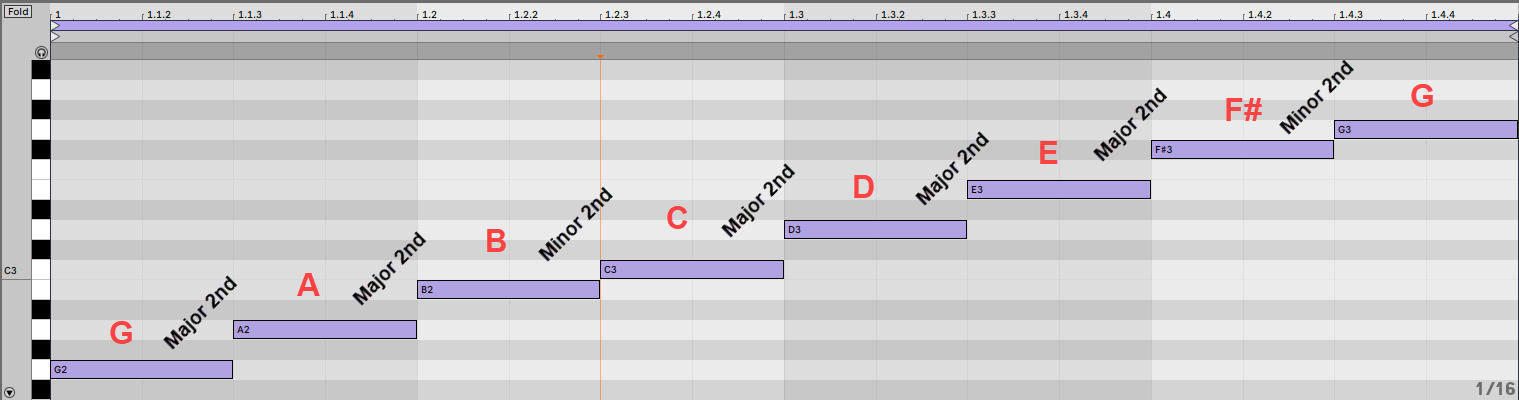

In order to build major scales on other keys, we simply apply the intervallic pattern we used to build the C Major scale on top of other notes, so for example, the scale of G Major would result in the following notes: G A B C D E F#.

Notice how now instead of seven natural notes, we get six natural notes and one altered note. That is because between the sixth and the seventh note of a major scale there is a major second, and between the notes E and F in their natural state, there is a minor second, so the F in G Major gets raised one semitone above its natural position.

C Major scale

G Major scale

That's it for the first part of this series on music theory fundamentals in which we have talked about core harmony concepts like intervals, inversions, scales and notes.

In the next part of the series, we’ll cover new topics like keys and diatonic chords, so stay tuned in order to gain further insight on how music composition and songwriting works.

Share this